Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

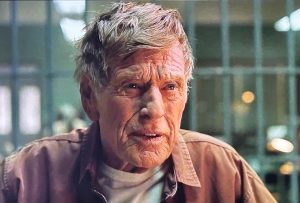

Photo: Robert Redford advocating against the demolition of Santa Monica Pier while filming “The Sting” on the pier. (Ken Dare / Los Angeles Times / UCLA)

Hollywood legend Robert Redford has died at the age of 89.

The longtime actor, producer, and activist passed away Tuesday in his Utah home.

Among the many things Redford was known for over his career, he was a champion of the environment and Indigenous rights.

Vincent Schilling, a journalist and CEO of Schilling Media, says the late actor launched many Native careers.

“It’s no question that Mr. Robert Redford did a lot to help Native people, look at the Sundance Institute. Native filmmakers, Native actors, constantly have posted about the things through Sundance. And he just continued to fight the right fight.”

Redford narrated the 1992 documentary “Incident at Oglala”, which investigated the 1975 murders of two FBI agents in South Dakota, and he was also an executive producer of the AMC mystery series, “Dark Winds”.

In the third season premiere, he made a cameo appearance as a jailbird playing chess with another prisoner, played by George R.R. Martin.

Lt. Joe Leaphorn, played by Zahn McClarnon, watches on.

- (Courtesy AMC)

- (Courtesy AMC)

Again, Vincent Schilling.

“There’s no mistaking what a hit ‘Dark Winds’ is, my gosh. Robert Redford really did quite a bit to enhance the legacy of not just himself as an actor, producer, and filmmaker, but also the legacy of Native filmmakers and independent artists all over the world. He leaves behind a wonderful legacy.”

Native artists including Zahn McClarnon, Sterlin Harjo, and Kiowa Gordon have all paid tribute to Redford on social media.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

Graduates of Red Cloud Renewables third Pre-ARP cohort of 2025. (Courtesy Red Cloud Renewables / Facebook)

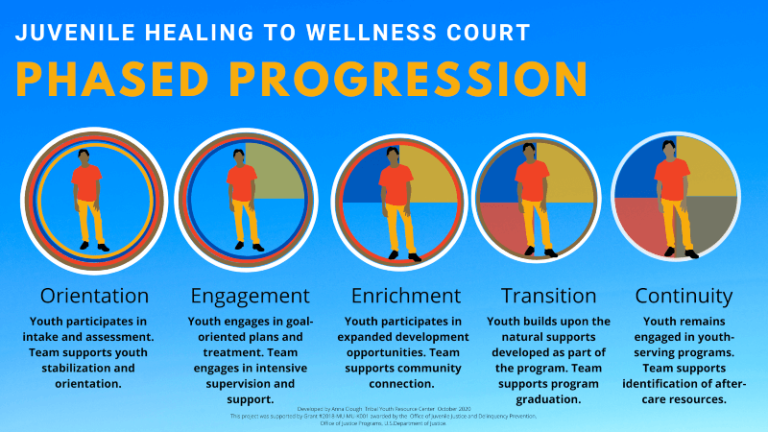

South Dakota is a prime candidate for renewable energy developments like solar. However, one group wants to make sure that power – and career potential – reaches every corner of the state.

SDPB’s C.J. Keene has more.

Pine Ridge-based Red Cloud Renewables has just welcomed its fourth wholly Indigenous cohort into its pre-Apprenticeship Readiness Program (ARP) for the year.

After the program, participants are “rooftop ready” to install solar panels as a career.

Alicia Hayden is the group’s communications manager. She explains how the program works.

“They learn basically everything there is to know about being a solar installer. They stay here on campus, so we give them gas money to get here or buy them a plane ticket to get here. We give them meals, we provide lodging, everything is free to the individual. When they leave here, they’re ready to enter the workforce.”

There’s more to it than just helping people find career paths though.

“Separately from our pre-ARP, we run a weatherization program which allows us to have this cache of community members we know are struggling with their energy bills. So, we select an applicant out of there and then nearing the end of this we take the class there, to their home, and get the class on the roof and install solar panels for them, and its free for the homeowners as well.”

Hayden says the projects actively lower the cost of energy bills for families in need.

“Especially on this reservation, there’s so much energy hardship and there’s so much sunshine and so much open space. When you drive through the reservation, you hardly see any trees and hardly anything that blocks out the sun. When we install these panels, we see a huge decrease in energy bills on our side of things. There’s no better place for a program like this.”

This program is funded through grant dollars and public funds.

In total, the group plans for seven pre-ARP programs by the end of the year for 100 total trainees.

Get National Native News delivered to your inbox daily. Sign up for our daily newsletter today.