Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

(Photo: Brian Bull)

During World War II, at least 100,000 Japanese Americans were forced into so-called internment, or concentration, camps across the U.S.

Seen by the government as a potential threat within America’s borders, memories of the mass incarceration still burns hot for former prisoners and their families.

Senior reporter Brian Bull of Buffalo’s Fire reports on a Native American college that held a special dedication that preserves that history.

About 200 people gathered at the Snow Country Prison Japanese American Memorial last Friday at the United Tribes Technical College (UTTC) in Bismarck, N.D.

Taiko and Native drummers performed together as dignitaries honored the 1,800 and 50 Japanese men who were confined here back when the site was known as Fort Lincoln.

(Photo: Brian Bull)

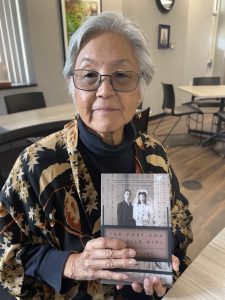

Satsuki Ina was born in a California camp in 1944, and her father, Itaru, was kept at Fort Lincoln in 1945 through 1946.

Her book, “The Poet and the Silk Girl”, is a memoir based on her parents’ letters, diaries, and her father’s haiku.

The memorial is the culmination of 25 years that Ina and the UTTC worked together to preserve this history.

(Photo: Brian Bull)

“There were trees that the Japanese American prisoners had planted. And there’s this story that there were ghosts that wandered around, and that when the wind blew on these trees, it sounded like somebody was crying. And so there was actually a healer that would come every once in a while and bless those trees. And so when I heard stories like that, I felt like the memory of their presence was really being protected and honored by the people here.”

Ina says there are efforts by the current administration to erase or dismiss past atrocities against communities of color. So she sees the UTTC’s support – including giving some of its property to the memorial – as key to keeping history accurate and the government accountable.

“This is, in many ways, an act of solidarity with the Native people and the Japanese Americans. And the lesson is, it’s in our collaboration, our solidarity with each other, that we strengthen our truths. And stand in opposition to efforts to erase our history, to alter it, to rewrite our narratives in way that, in ways that don’t talk about the truth.”

At the end of the dedication ceremony, a Japanese and Native flute player performed together, as visitors placed paper cranes on the names of those incarcerated at Fort Lincoln.

Those were inscribed on slate tiles that once lined the barracks.

Tylar Larsen, center, has been a counselor at the Oscar Howe Summer Art Institute for five years after being a student for two. (Photo courtesy University of South Dakota Department of Art)

Over the summer, at the University of South Dakota, 20 high school students attended the annual Oscar Howe Summer Art Institute, learning from each other and renowned Native American artists.

Mike Moen reports.

The camp’s inspired by artist Oscar Howe, who paved the way for Native artists to challenge stereotypes, teaching at the university for more than two decades.

Instructor Keith BraveHeart helps students learn about Howe’s approach to art, recounting his first experience with the trailblazer’s legacy.

“It felt like the work was alive, like it was physically breathing; like it was pulsating. And I know that it could have been an optical illusion because of the way that he designs his work, but I also later would truly believe that it was imbued with a Dakota spirit.”

BraveHeart studied in one of the institute’s many iterations as a student.

“I see this potential that what was my path, my journey, what that could be like, might be similar to a next generation of an artist, a younger artist.”

A citizen of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, BraveHeart says he thinks creating those future pathways is what Oscar Howe envisioned.

This story was produced with original reporting from Amy Felegy for Arts Midwest.

Get National Native News delivered to your inbox daily. Sign up for our daily newsletter today.